The Yorkshire Arts Association – Foundations – Part 4 – Major Production

A Great Effort (c/o Sheffield Hallam Special Collections)

With Alf Bower and the Yorkshire Communication Centre (YCC) established as base (working in tandem with resource facilities, and people skills at Sheffield Independent Film - SIF), the Yorkshire Arts Association (YAA) Film Policy and application process now in motion, Pearse and the Film Panel began the Major Productions rollout.

Yorkshire Arts Press release for YORKSHIRE PROJECTOR

One of the most interesting schemes of this era was the Yorkshire Projector film programme. The vision behind it was to capitalise on a wave of YAA short films being produced in the region yet unable to gain access to market. Pearse decided that a sensible way of promoting this activity was to take these films and package them together, topped and tailed with a title sequence. They could then be distributed to film societies and RFTs. It is an idea steeped in the history of the mobile newsreel, a magazine format showing items of local and regional interest first established in the 1950s. The first edition screened via the North Yorkshire mobile cinema unit in December 1976 and was forty minutes long. It came loaded with a bespoke stop-motion animated title sequence of a puppet called ‘Albert’ made at the YCC on 16mm Bolex and accompanied by a specially shot advertisement marketing the services on offer at the centre.[1] Jim Pearse originally designed the Yorkshire Projector series as a four-times a year release, but in practice the series stopped at Yorkshire Projector #2. That the ‘series’ only reached edition 2, is indicative, perhaps, of ambition becoming outweighed by limitations in resource. Despite this, the press reaction was positive. Writing in a 1977 press release announcing the second edition, Pearse claimed that the Projector was ‘welcomed by the local and national press as an imaginative attempt to draw attention to the work of independent film-makers in the region.’[2] Its promotion of the word ‘independent’ is a further notable shift in the outward-facing semantics used by the YAA to describe film activity, and the three sophisticated films which make up Yorkshire Projector #2 point to a new future of this, more professional, independent film production.

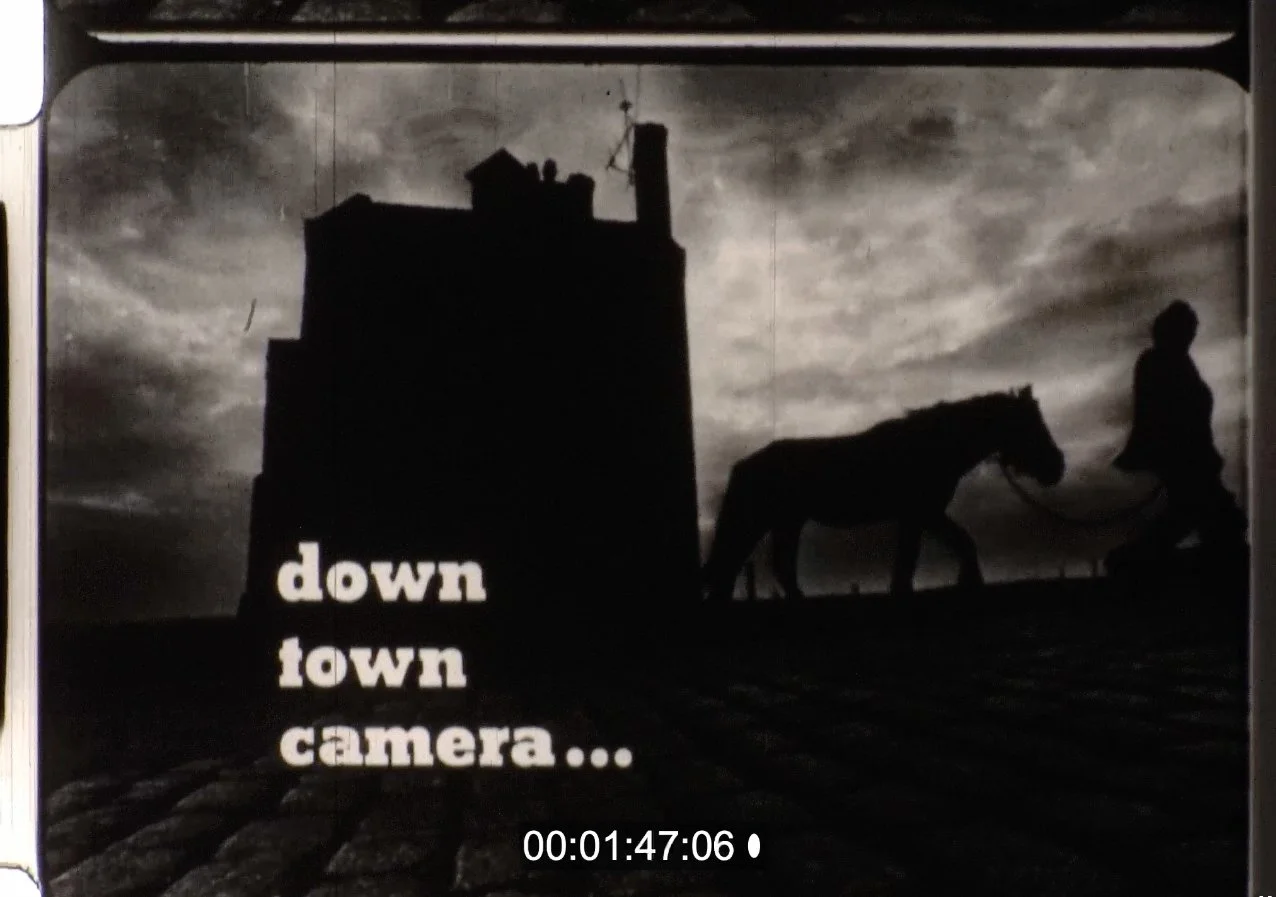

The newsreel leads with a film about a North Yorkshire festival by Peter Bell, followed by the second work from Sheffield Film Co-op about the harsh realities of domestic abuse (That’s No Lady), and is bookended by a stark documentary from Telegraph and Argus photographer, Andrew Yeadon. Downtown Camera is a 12-minute piece in vivid black and white, which follows Yeadon documenting the inner-city decay of post-industrial Bradford.

The film cuts together, sometimes harrowing, footage of the city to Yeadon’s photography - who also narrates: ‘I show my pictures to people, and they say, “Where’s that? Not Bradford” and I say, “It is… you’ve just not seen it.”’ Downtown Camera is a bleak picture, shot with composure and empathy by Yeadon, showing the city and its characters in a state of decline, poverty and unemployment. Yeadon was only 24 at the time of Downtown Camera, and after further training as a news/documentary photographer and journalist on London newspapers, he joined Haymarket Publishing as chief photographer on Autocar magazine. He has since worked freelance, specializing in automotive, travel and lifestyle photography with work published globally.[3]

Where Downtown Camera presents Yorkshire’s post-industrial urban spaces, a number of projects endorsed by the YAA during the latter half of the 70s were concerned, in differing ways, with the rural landscape and the outdoor environment. The legacy of films using outdoor spaces in Yorkshire, dates to the silent era. The Sheffield Photo Co. were one of the first film companies in the UK to exploit the potential of outdoor filming: ‘liberating their films from the painted back drop production, and moving outside, this strategy was soon cop-opted, however, especially in the States.’[4] This method of working was sadly not sustainable, however, as the South Yorkshire climate dictated that too many shoots were called off.

Nonetheless, fast-forwarding to the 1970s, Yorkshire’s filmmakers were undeterred by the elements, and the jagged cliff-sides of the Peak District and North Wales provided the backdrop for Jim Curran’s first film, A Great Effort. Curran was student at Sheffield City Polytechnic under the tutelage of Paul Haywood. He was also keen climber. Using the 16mm facilities at college he based his first short film on the writings and poems of John Menlove Edwards, a pioneering climber of the 1930s and 40s. The film intercuts period photographs of Edwards, music by Curran’s brother Phil, and recited poetry narrated by Derek Allport to images of Curran himself traversing the same climbs and descents which Edwards charted in the 30s.

A Great Effort (c/o Sheffield Hallam Special Collections)

Tony Riley’s 16mm camera watches Curran from a distance, and in tight focus, as he attempts the notorious peaks. While the film is credited as ‘A Sheffield Polytechnic Production’, Curran had to apply to the YAA for completing the picture. £2986 was awarded in 1978, to go towards editing, sound, processing and distribution.[5] With this assistance toward ‘completion costs’, a familiar pattern was being established. The initial processes of film-making (writing, pre-production, planning, casting, recruitment, shooting equipment etc) were often self-funded, or in the case of A Great Effort assisted by an institution like Sheffield City Polytechnic. However, under Pearse’s new policy if a film project displayed enough potential, it would be granted completion money to aid the complex and costly mechanics of film processing, editing, distribution and marketing.

Curran soon followed A Great Effort with a further YAA funding contribution for his climbing film based on famous mountaineer Robin Smith's tale The Bat & The Wicked, interwoven with extracts from Dougal Hastons's autobiography In High Places.[6] The Bat (1978) was shot in the Scottish Highlands, and won Curran (and cast, Rab Harrington, Brian Hall) Grand Prize, Kendal Mountain Film Festival (1980), and Best Climbing Film at the Banff Mountain Film Festival in 1981. Jim Curran made many more mountaineering films throughout his career and wrote books on expeditions to the K2 and the Himalayas. Because of his contribution to the world of climbing and travel writing he was given the Boardman Tasker Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014. He died in 2016.[7] A Great Effort is a powerful work of technical ability and visual poetry. It remains one of the strongest YAA films of the late 70s - made even more remarkable given Curran’s status as a young student at the Polytechnic. A Great Effort / The Bat cameraman, Tony Riley used these experiences as a springboard and began working freelance in the 1980s as cameraman for Panorama and ITN. He also crewed for the Sean Connery film feature, 5 Days One Summer (1982).[8]

From the great outdoors to the underground, Speleogenesis is an ambitious experimental film by the caving camera team of Lindsay Dodd and Sid Perou, which traces the course of an underground river in the potholes of the Yorkshire Dales, with electronic score by ‘No Music Ltd’. Having worked alongside experienced caver Lindsay Todd on the 1976 ITV series Beneath The Pennines,[9] Perou and Todd applied to the YAA for £1,000 to realise their technically complex trip underwater. Perou is insistent that the YAA was an integral ally: ‘the beauty of the idea was that we would not need the army of helpers we had to recruit for Beneath the Pennines and we would have complete creative control throughout both the filming and the editing.’[10] Joined by cameraman Geoff Yeadon[11] the final production took two years to film, and the result, after editing at Leeds University, is a remarkable feat of technical competence as the camera snakes its way through spaces which at first appear to be impenetrable. Meanwhile, a rumbling electronic score is cut in strange rhythm to the visuals. While the film had limited release commercially, it received great recognition in the caving world, winning several awards including the Grand Prix and the Public Prize at the International Caving film festival, and at the Espelio Cinema Barcelona festival in Spain. After the experience of working for a mainstream broadcaster on Beneath The Pennines, Perou remembers the YAA-backed Speleogenesis fondly: ‘having been sucked into the glamour of commercial television, used, abused and spat out again, I was hankering after the experience of those special days of pure unadulterated creativity and I got that from this film.’[12] This quote undoubtedly speaks to the security of working in the less-pressured frameworks of grant-aid YAA organisations as opposed to the high-stakes, deadline-centric world of broadcast. Perou is not the only interviewee active in this period to take this stance.

Formed in Mytholmroyd 1976, IOU Theatre Company are an arts organisation based in Halifax and still active. In the late 70s and 80s they worked alongside prominent artists, actors, dancers and filmmakers in the region to explore work at the intersection of live art, theatre, dance, sculpture and music. A fertile interrelationship between theatre, performance, dance, musicians and filmmakers emerges; one that brought together individuals from all disciplines, organisations, and even different parts of the region. At the heart of their practice was the adaptation of ‘landscapes and locations for performances that fuse many aspects of the arts into one poetic whole … building a theatre unique to the location and occasion.’[13] In an YAA application the company make the suggestion that ‘film is ideally suited to both develop and to portray the work of IOU.’[14] Much like the use of the video medium to record community theatre by Albert Hunt at Bradford, IOU adopted the 16mm camera as creative tool to capture their unique site-specific performances, using the landscapes of Yorkshire as backdrop. An early example of this is Arrival of The Iron Egg (1976). The surrealist short uses ‘uses live action and animation to depict the arrival of an iron egg from outer space’ and was first shown in Hebden Bridge at IOU's pantomime Captain Goat's Parrot.[15] Credited on the film are Sheffield Polytechnic’s Barry Callaghan and Paul Haywood, avant-garde saxophonist Lol Coxhill (who was at the vanguard of British improvisatory music), Cumbrian performance collective, The Welfare State International, and future Professor of Film Studies at the University of London and Screen journal figurehead, Annette Kuhn. The animation elements of …Iron Egg were created by cartoonist and film-maker Brodnax Moore who also directed the live action recording at Ingleborough, North Yorkshire.

Towers - https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-towers-1977-online

A similar cast of players would return to the wilds at Brimham Rocks for the next Moore / IOU collaboration. Towers (1977) was an IOU show originally created to be performed on Brighton beach, while a version was also filmed at Bolton Abbey and toured the region with funding assistance from the YAA.[16] The finished film (subsequently restored by the YFA/BFI) is a rare glimpse into IOU’s strange and ritualistic performance art. In 1978, IOU submitted an application to the YAA for another ambitious performance/ film project again using the county landscape as its main ‘character’. An Example Of Zeal was proposed to the YAA as a witness to the ‘entire working process of an entire IOU piece’, with use of film to show ‘its audience aspects of the work that are not normally seen’. Elaborating on the potential of film, IOU declared that this project would ‘give them the opportunity of using cinematic grammar not possible in theatre, such as big close-up tracks and cranes, instant scene changes and intricate picture and sound editing’. The total proposed budget for the project was £3484 and was submitted to the YAA in 1978. Included in that cost was a wage provision for a film crew, and associated equipment and process costs. In the application IOU were keen to emphasise the collaborative nature of the project, in doing so they stated that there would be a ‘broadening of ideas between IOU and the film-makers on possible future ways of working’. They recruited two members of the YCC team (Alf Bower, Jim Pearse) and three members from the SIF collective (Moya Burns, Peter Care, and Russell Murray) to work on script and budget development. The group helped on the final film production which follows the costumed IOU performers from their base at the Mill in Mytholmroyd across the moors, in preparation of the final act at the World Theatre at Nancy, France (the film never reaches Europe). It is a surreal vision into the group’s process and uses live music (later dubbed at the YCC) and dance at its centre.

In many respects, the IOU experience represents a fine example of the notion of creative collaboration at the centre of YAA sponsored film and video in the 1970s. Example of Zeal is the distillation of the collaborative element of the competitive collaboration formulation, and in many ways represents the apex of the post-68 countercultural activities being supported by the YAA Film & TV panel, before the YAA pivots to a more ‘professional’ way of operating in the during the 1980s - the professionalism vs. counterculture dichotomy in plain sight. Although Pearse said of the old application process ‘that loose kind of anarchic grant-aid model didn’t work anymore,’ IOU’s oeuvre was, in many respects, the distillation of the word anarchic. Despite being part of the formal application regime, their methods of cross-discipline, mixed media production resonate with the loose and ragged spirit of the alternative society; the ethos of arts-labs, and the avant-garde as described elsewhere. It is telling that ongoing YAA support for IOU in the 1980s remained, but it was not provided by the Film & TV panel, rather it was subsumed into the theatre and performance funding board (traditionally the domain of the ACGB backed disciplines).

Black Future (Jim O’ Brien)

During this time, another film in Bradford was a made. Facilitated by the Hunt-led Media Education Unit (MEU), and financed partly by the YAA, the Gulbenkian Foundation and the Commission for Racial Equality, Jim O’Brien’s film Black Future meets a group of unemployed young West Indians in Bradford who create a science-fiction drama (a film-within-a-film), about a Britain ‘as it will be in 1983, with two million unemployed and the country divided into welfare zones.’[17]

James (Jim) O’Brien trained at the Guildhall as an actor before joining the Nottingham Playhouse enjoying a succession of well-received performances as actor and director. He then became Artistic Director at a theatre for new writing in Soho, London and retrained at the National Film and Television School (NFTS). Perhaps due to his connections to community theatre in Nottingham, he found himself working with Albert Hunt at the MEU in Bradford and devised the Black Future project. Interviewing a body of local youth about poverty and unemployment in the city (while showing a series of statistics about joblessness), he then boldly takes the same group of youths to a dystopian future of 1983, as the group act out (and film) an even bleaker existence than the one they find themselves in in 1977.

O’Brien finishes his film with a sobering follow-up on the protagonists’ lives after production. The YAA financed the film to the sum of £1400. As a testament to the polished final production, Black Future was later shown on BBC2’s community access programme, Open Door, in November and December of 1977 and screened at Newcastle, London, and Oxford film festivals.[18] It remains an honest - and prescient - snapshot into the lives of inner-city youth and the struggle for employment in the post-industrial towns of the North. O’Brien himself had a glittering career in the 1980s, working for the BBC (he is perhaps best known for the drama series, Jewel In The Crown, 1984) and adapting a Beryl Bainbridge novel for feature film (The Dressmaker, 1988). While his direct connections to the YAA and the region itself seem limited, in many respects Black Future is one of the standout films of the period, and it is evidently the work of a film-maker heading to bigger budgets, the BBC, and London.

The Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, filmed Khoon Aur Paisa/ Blood and Money (1977) has the significant claim to being the first Bollywood, Hindustani language, film made in the UK. It was an arduous journey to the final production and is worth discussing here. What makes this film so startling is evidence accrued already in this thesis that points to a filmmaking culture in Yorkshire which was largely dominated by white men (and some women) from the educated middle classes, and so Khoon Aur Paisa/ Blood and Money stands as a hugely notable title, being the first YAA sponsored work by a person of colour. The idea for the film was first devised by Gucharan Gossal in 1974 and he spent over two years in script development and pre-production. Gucharan moved to Huddersfield when he was eight and had his first experience of the theatre at Venn Street Arts in his teenage years. In the 1970s he set up the film group, Indian Arts in Huddersfield, where he pooled together a cast and crew for his film plucked from local members of the Birkby Youth club. The collective first experimented with 8mm but finding no means for synchronised sound they applied for a loan of video equipment from the YCC. Here, they found more issues as editing and playback on the clunky 1” video-tape format proved troublesome. However, the format proved useful in recording rehearsal sessions, allowing the cast and crew to hone the script into a working fashion. Finally, submitting a grant to the YAA for 16mm facilities, the panel gave Indian Arts £328 toward production costs,[19] which is notably meagre compared to similar productions of the time. Integral to Gucharan’s learning process was the help of experienced YAA panel member John Murray. He was a filmmaker who had a long career as the principal photographer on the newsreel project ‘Picture Post’ and in 1970 joined the Film Unit at Leeds University to run the Audio-Visual Service. He became the Chair of the YAA Film & TV Panel in 1978. Murray also operated camera for Khoon Aur Paisa, and assisted Gucharan in the more complex parts of the production.

John Murray & Gurcharan Singh Gossal (Khoon Aur Paisa-22 May 1977)

The finished thriller is mainly shot in and around Huddersfield and features Gucharan in the lead role, with other parts played by brother Surinder and Parveen Shafi, a Leeds University student. Khoon… speeds along its hour duration as ‘we get involved in a drug racket, a rape, several fights, and considerable discussion on the virtues of family ties as against the pursuit of wealth,’[20] and is packed with exciting set-pieces and ambitiously choreographed song and dance routines (there are four newly composed original songs).

Although it is a work of fiction, Gucharan suggested at the time, ‘it is based on social problems which do really exist for young Asians living and growing up in Britain.’[21] Once production was finished the rushes were edited at Leeds University, and the soundtrack dubbed at the YCC. However, the group did not have enough money to print a distribution copy. They successfully applied to the YAA for a follow-up grant to facilitate this process, and after the panel saw a preview print of the film, awarded the funds of £285. This remarkable achievement (made for under a thousand pounds) is testament to the craft and hard work of Gucharan Gossal and his team, including the experienced John Murray guiding the crew through almost three years of production. While the film only toured regionally to limited circulation, Gucharan relocated to Bombay in the 1980s and forged a successful career as Bollywood actor/director. Ironically, given the early genesis of Khoon Aur Paisa, it was the advent of video which sparked his lucrative career in India, as the straight-to-video market facilitated his future path in film.[22] The lack of exposure for Khoon Aur Paisa is indicative of a number of factors.

In the simplest terms, the non-English language nature of the film meant smaller potential fro distribution channels than other YAA films of the time. It was not subtitled, and so cinemas were simply not equipped -or willing- to play the film to what was likely a small second-generation immigrant population seeking to visit cinemas (that is even if they heard about the film). Secondly, the ‘straight to VHS’ market which Gossal thrived in during the 80s was not around during the time of Khoon Aur Paisa; this would have been a more obvious distribution platform for the film, enabling it to reach audiences who could interpret the language without captions Thirdly, the inescapable fact is that despite these two late 1970s titles (Black Future and Khoon Aur Paisa), which sought to represent second generation immigrant communities in Yorkshire’s urban centres, the trajectory of YAA filmmaking (and audiences) in this thesis remained the reserve of white men and women from the middle class. The meagre YAA budget given over for Khoon Aur Paisa is perhaps evidence of. All these factors, sadly, illustrate the pervasive theme of archival absence. At the time of writing, the original prints for this title have long been missing and long sought for preservation by the YFA and elsewhere. All we have as reference is a wobbly full film VHS transfer uploaded nearly a decade ago to YouTube. Why is this film not safeguarded by the BFI, by the YFA? Why has the story of its creation been left to vanish? Where is it? Gucharan Gossal passed away sometime in the 2010s, and frustratingly little has been written about his life and legacy as a British Asian film hero. Hopefully this can be rectified.

Footnotes

[1] Jim Pearse Interview.

[2] Press release YAA unpublished. 1977

[3] http://andrewyeadon.com/

[4] Robert Benfield p 15.

[5] YAA Report.

[6] https://steepedge.com/categories/culture-films-movies/culture-films-movies-the-bat.html

[7] https://www.ukclimbing.com/news/2016/04/jim_curran_tribute_to_a_renaissance_man_of_climbing-70385

[8] SIF Archive, Sheffield Hallam Special Collection, ‘Notes on a Sheffield Independent Film Catalogue, 1984’ (Anon. 1984).

[9] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b5eoZd-nyBE

[10] Interview /email Sid Perou

[11] (no relation to Andrew),

[12] Interview /email Sid Perou

[13] IOU/Example Of Zeal flyers / Alf Bower archive

[14] ibid/ IOU Alf Bower

[15] https://www.yfanefa.com/record/11983

[16] https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-towers-1977-online

[17] Quote from film, Black Future

[18] Radio Times - Genome

[19] Huddersfield Examiner, June 11 1976

[20] Yorkshire Arts Magazine, Arts Yorkshire, June 1976

[21] Huddersfield Examiner, Sep 4 1976

[22]Huddersfield Examiner - Date Unknown